Wednesday this week (I’m on Spring Break) I had an unexpected opportunity to visit the Dixonville Cemetery in Salisbury, North Carolina, about 45 minutes north of Charlotte. I drove past the cemetery after an appointment at the Salisbury Veteran Administration (VA) hospital complex. From the mid-1800s until the 1960s, the area served as an African-American burying ground, including slaves and their descendants.

According to the Dixonville-Lincoln Memorial website, maintained by the Dixonville-Lincoln Memorial Task Force and the City of Salisbury:

Burials occurred here from the mid-1800s to the 1960s, when much of the neighborhood was pushed down in the name of urban renewal. There are some 500 documented burials here since 1910, based on local historian Betty Dan Spencer’s research. But there were likely hundreds more. The oldest gravesite known is Mary Valentine’s, who died in 1851. Some of the more prominent African Americans in Salisbury are thought to be buried here. They include Bishop John Jamison Moore, who founded the AME Zion Church in western North Carolina; and the Rev. Harry Cowan, a legendary minister who was born into slavery but went on to establish 49 churches and baptize 8,500 people. It was Cowan who after the Civil War and emancipation established Dixonville Baptist Church, which became today’s First Calvary Baptist, standing just north of the cemetery.

City of Salisbury, NC. (n.d.). Dixonville Cemetery. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://dixonvillememorial.com/Cemetery

I recorded a 4 minute video during my visit to Dixonville Cemetary on Wednesday, and read the “Path to Lincoln School” historical marker which is adjacent to the cemetery.

I also took and shared a number of photos of the cemetery and surrounding area, which I posted to a Flickr album.

The Dixonville Cemetery lies right next to The Lincoln School, which was known as “The Colored Graded School” when it was established in the 1880s as the first school for African-Americans in Salisbury, North Carolina.

In an ironic but historically appropriate way, the boarded up / dilapidated Lincoln School / “The Graded Colored School” is situated next to the immaculately maintained and solemn Salisbury National Cemetery, which was established after the US Civil War to bury thousands of northern, Union soldiers who died in the Confederacy’s POW Camp operated in Salisbury until 1865.

I also recorded a video reflection from the Salisbury National Cemetery, and I will share a separate post about that experience and my reflections here later.

There were many reasons the opportunity to visit both Dixonville Cemetery and the Salisbury National Cemetery this week were catalysts of cognitive dissonance as well as reflection for me. One reason was the jarring difference between the number of headstones / gravestones in each cemetery. There are hundreds of buried African-American bodies beneath the ground at Dixonville Cemetery, yet there are just a few headstones / gravestones.

Sadly, recent vandalism (in February 2022) contributed to this historical dearth / lack of headstones for buried African-Americans in Salisbury. The biggest reason slave cemeteries like these do not have many headstones, however, is basic economics: Enslaved African-Americans did not have the financial resources to purchase, manufacture, and maintain cemetery headstones. Many of their ancestors and other African-Americans buried in these spaces in later years did not either.

While there are major physical, visible differences between these adjacent Civil-War era cemeteries, there are also striking similarities. An unconfirmed number of US soldiers are buried in the Salisbury National Cemetery, likely numbering into the thousands. Thousands of those are UNKNOWN Union Civil War soldiers. Similarly, an unconfirmed (and likely unknowable at this point) number of enslaved African-Americans and descendants of African-American slaves in Salisbury are buried at Dixonville Cemetery.

Both of these cemeteries are sacred spaces. Both have their origins in the mid-1800s, in the events surrounding the U.S. Civil War. The land and the spaces of these cemeteries are heavy with history and the legacy of bitter struggle. While one space is largely empty, the other is filled with white, granite headstones and replete with patriotic phrases and sentences conveying valor, patriotism, and remembrance.

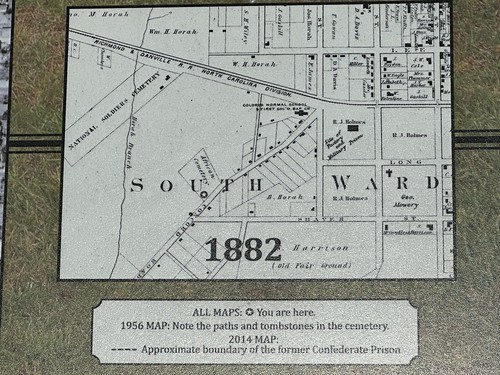

As a geographer and life-long lover of geo-spatial representations of complex ideas, I was immediately drawn to the series of three maps which show the Salisbury neighborhood in which Dixonville Cemetery and The Salisbury National Cemetery are located.

The map of the “South Ward” in Salisbury.

The 1956 map of the neighborhood before “urban renewal” wiped out many African-American homes starting in 1963, eventually demolishing 230 structures and replacing them with “new public housing.”

Lastly, the 2014 map showing the current boundaries of the Dixonville-Lincoln Memorial as a white, dotted line.

This screenshot shows the latest Google Earth view of the Dixonville Cemetery area and neighborhood. The large buildings shown above the Salisbury National Cemetery have been demolished, however, so this enhanced satellite image is not entirely current.

There are MANY thoughts and reflections I have regarding these sacred and historic spaces in Salisbury, North Carolina. One of this most important is summarized well by this quotation on a bench located at the edge of the Dixonville Cemetery.

“We have to have the courage to just say hey, today, I’m tellin’ my story.”

by Timika Peterson

As an immigrant storychaser and teacher from Oklahoma, I’m eager to connect with other community activists and students of history in the Carolinas, to share together the stories of our communities, neighborhoods, state and nation. We live in a challenging time, where some voices in our ongoing “culture war” discourage us from discussing and exploring difficult eras of our shared history like the transatlantic slave trade, the U.S. Civil War, and systemic racism.

We cannot and must not remain silent about these issues and important topics. Physical, sacred spaces like Dixonville Cemetery and the Salisbury National Cemetery can serve as catalysts for us individually, and corporately, to confront, process, and learn from difficult events and experiences from our collective past.

This landscape is rich with opportunities for digital storytelling, storychasing, GeoMap creation and sharing, and simply walking or sitting outside in historic places, feeling and welcoming the weight of responsibility which is ours as stewards of our communities and planet.

We have important work to do together.

Leave a Reply